For this sketch, I decided to delve into the details of how we perceive the passage of events over a short period of time. Please allow me to guide you on a series of thoughts related to time my investigation into detecting changes that occur in units smaller than a second.

I first thought of exploring this idea after thinking back to working at a historic movie theater in Ann Arbor back in college; to set the scene, this was between 1996-1999 and the films we showed came in metal canisters with multiple reels per movie.

The lead projectionist there, Walt, was telling me about how the timing of the reels worked. Because there were traditionally two projectors to switch between, projectionists needed to keep an eye on the reels and the ‘cue-dots’. (You may remembering seeing something about this in the movie Fight Club.)

Here are some details from an online manual on how to screen a 35mm film from an MIT lecture series:

The end of each reel is announced by cue-dots. Typically the first cue is eight seconds before the end of the reel and the second cue is one second before the end. A cue-dot is a circular or oval dot, usually black in color, visible in the upper right-hand corner of the image, and lasting for approximately 1/6 of a second (four frames at twenty-four frames per second). Also, remember that each new reel is projected on the previously-idle projector, so noting which projector ran the first reel may be helpful.

To bring this back around to this sketch, I’ve often thought over the years about how seamless movies on film appear even though are they are just a succession of image frames. This trick of creating the illusion of a flowing image lies in finding the perfect speed (images, or frames, per second) to project the series of images.

Obviously, if you’re shown a series of images in succession at a rate of one per second, you’d notice the changes as being stepped, in succession (rather than being fluid and motion-like); think of watching the second hand on a quartz clock. Considering this, we know, as humans, vision-wise, we’re able to perceive things at rates faster than one per second. If you want to test your limits of perception, try the wobbling pencil trick.

If we go by the fact that, for many years, projectionists depended on cue-dots that appeared for approximately 0.167 seconds in a tiny corner of the screen to keep movies going in theaters around the world, we know cues shorter than even a ⅕ of a second are perceivable enough to be reliable. Interestingly, these short lasting dots were also engineered not to disrupt the feel/flow of the films projected, so there’s probably something to this sixth-of-a-second length.

With this in mind, I wanted to see if I could replicate this experience of flow/motion through a succession of images; I’ve also been trying to focus on more manually produced projects to keep me busy in the pandemic. Because of this, I decided to create a flip book, using a series of bird animations I found online as the basis of my imagery.

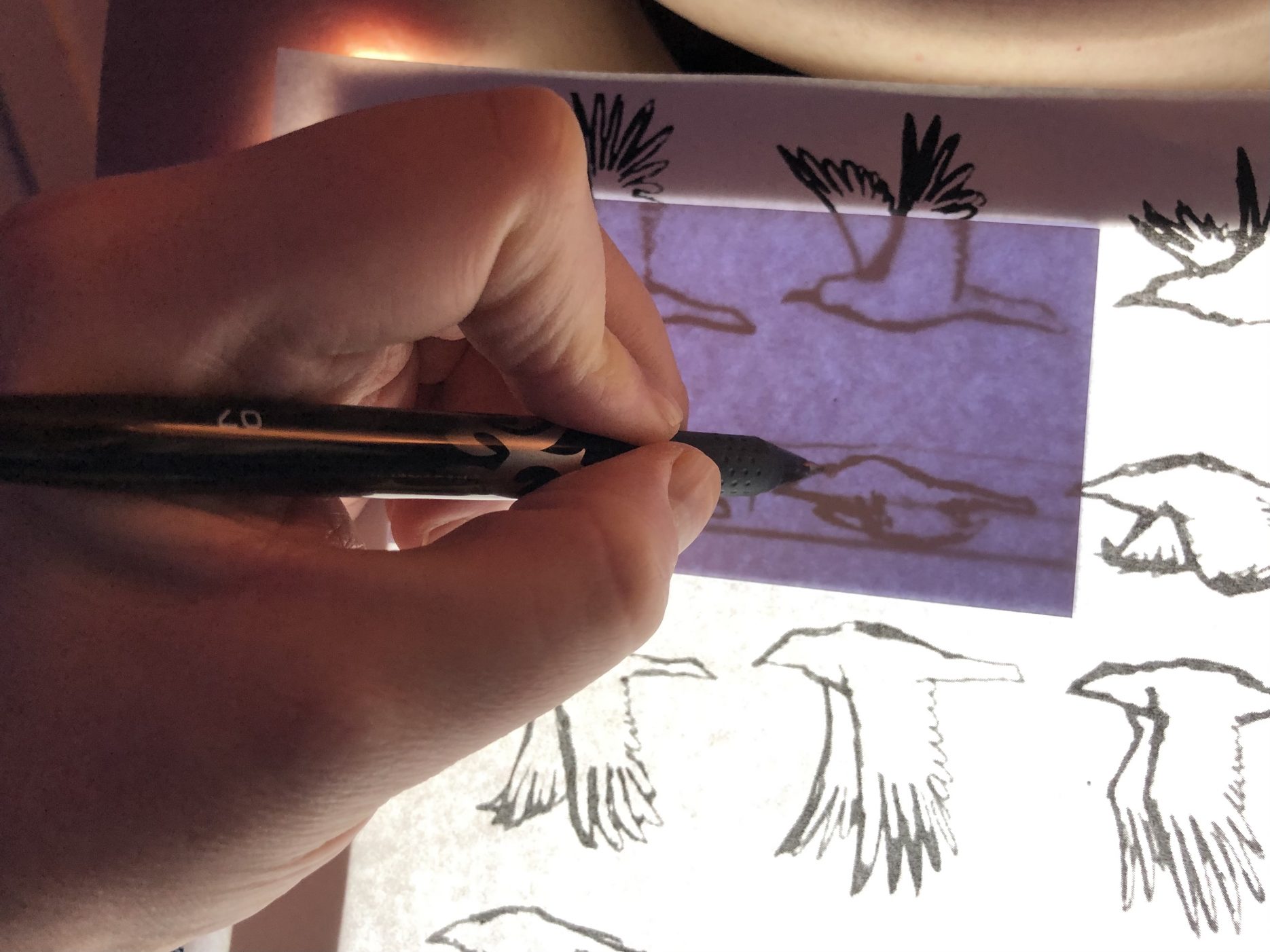

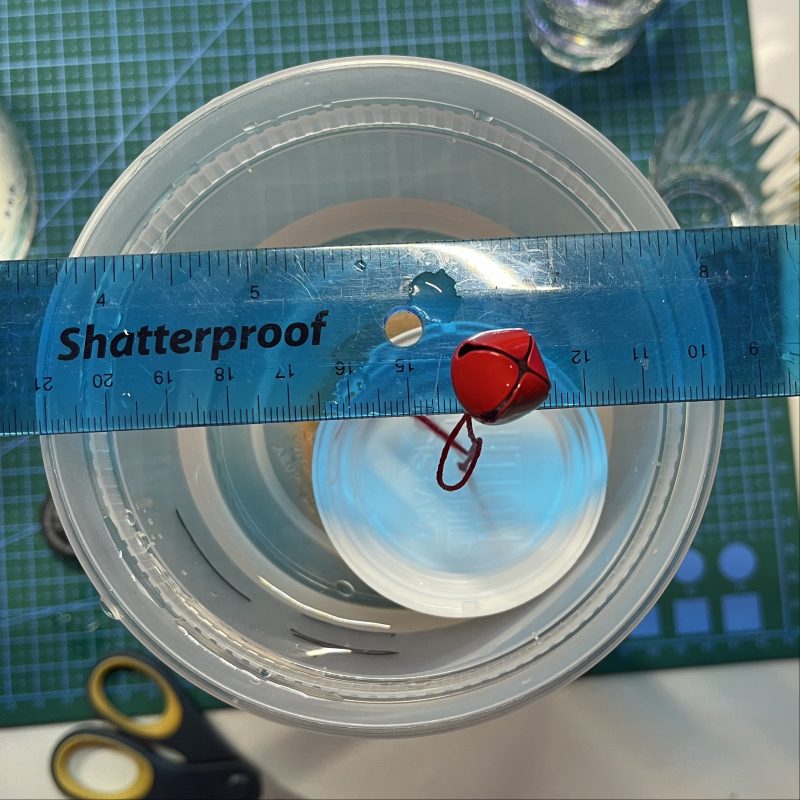

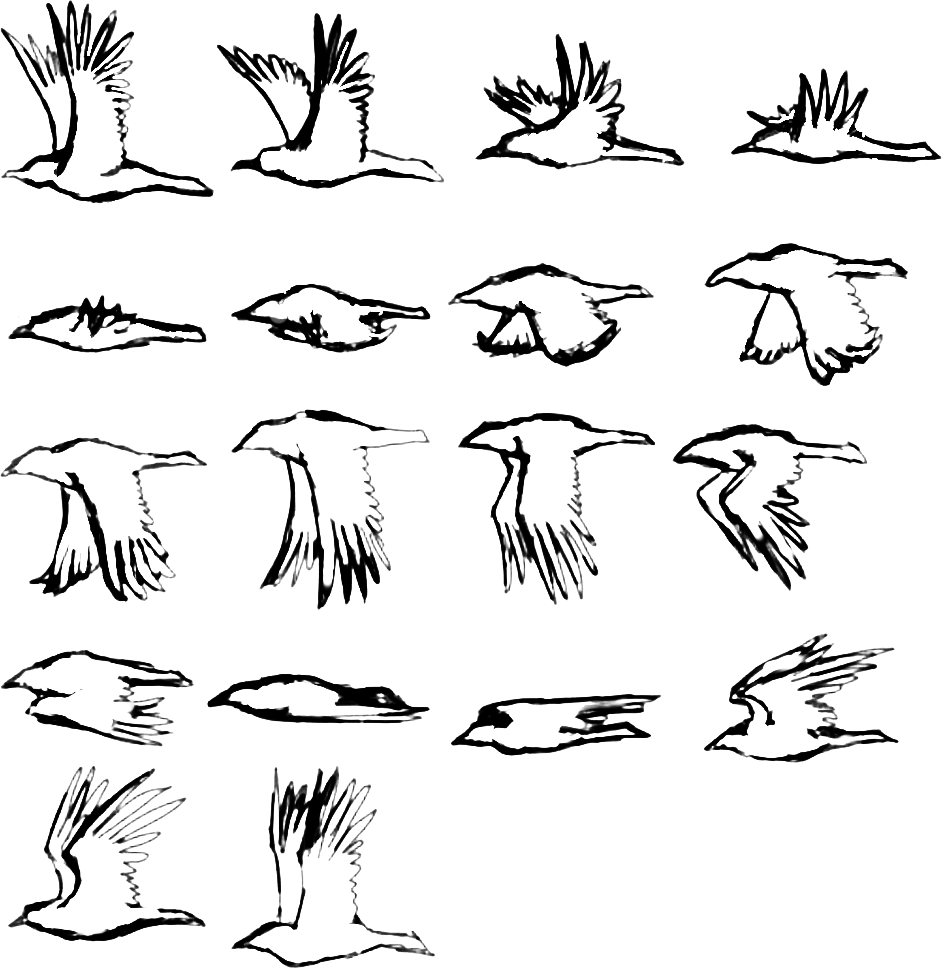

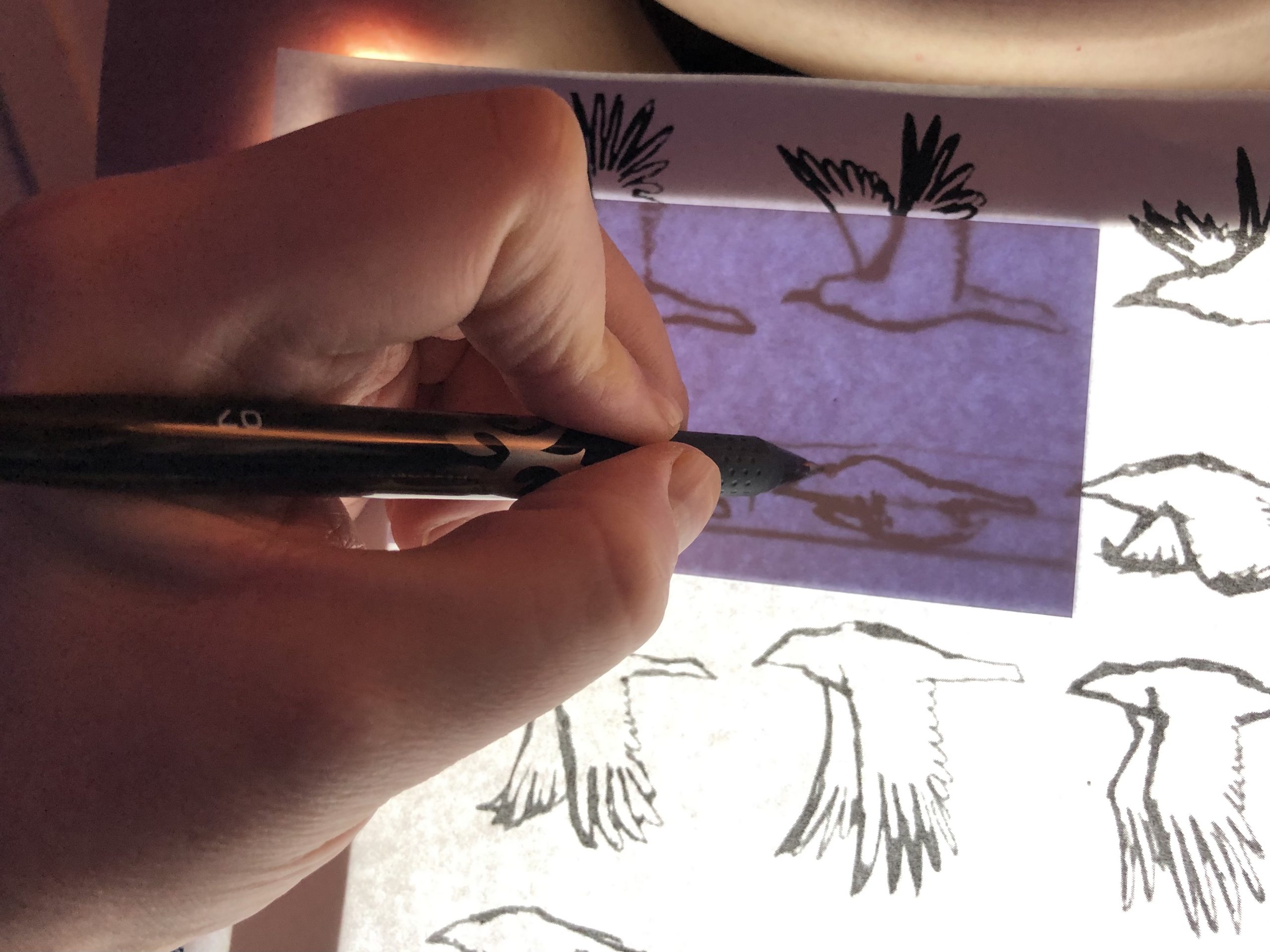

I cleaned up the bird animation frame drawings and enhanced their outlines in order for me to be able to trace them better. I used a light box I purchased online to help with the tracing process and created a series of guidelines which I placed under each page to know where to draw and position the birds. There were 18 birds in the series; I decided to have the animation repeat the images twice, starting with the first image, and continuing over four pages, having the bird entering the ‘scene’. Once there, the bird stays in place, flapping its wings, before flying off in a series of four final images.

Here is a series of videos in a YouTube playlist, showing a short flip through (recorded at a rate of 60 frames per second), the same short flip though (recorded at a rate of 240 frames per second and played back at 30 frames per second) at ⅛th the speed, and then a series of flip throughs of the flip book for documentation’s sake.

So, what was my experience making this? I feel like immersing myself in the minutiae that is creating each frame gave me a greater appreciation of this phenomenon. Keep in mind, the entire length of the book time-wise (as animation experience) was less than two seconds and creating the effect took me 40 drawings and close to two hours to get it right.

I was surprised how well the effect was conveyed considering how deformed-looking most of my birds were; some alone would surely not be recognizable. I think heavily coming into play here is context, as virtually all of us have seen a bird.

Armed with my past and recent experiences, I was curious to learn more and take this sketch as an opportunity to further explore the idea of perceived continuity, asking things like:

- how is that we have come to use the unit of a second if we can perceive things at shorter intervals/faster speeds?

- what happens when we play in the spaces between our ability to consciously perceive? Specifically, are subliminal messages effective?

- what are some other devices, like flip books and film projectors, that play with this idea of frames per second?

Here’s some of the interesting information I came across, along with resources worth checking out if this subject interests you:

- According to Wikipedia: “Originally, the second was known as a “second minute”, meaning the second minute (i.e. small) division of an hour. The first division was known as a “prime minute” and is equivalent to the minute we know today… The factor of 60 comes from the Babylonians who used a sexagesimal (base-60) numeral system.”

- The Frame Rate listing says of our perception capabilities that “the human visual system can process 10 to 12 images per second and perceive them individually, while higher rates are perceived as motion.”

- Referring to subliminal messages in video, “subvisual messages [are] visual cues that are flashed so quickly (generally a few milliseconds) that people don’t perceive them.”

- The effectiveness of subvisual messaging is debatable. James Vicary claims he exposed close to 50,000 people to subvisual messaging encouraging moviegoers to “Eat Popcorn” and “Drink CocaCola”, which caused sales of both to jump; however, Vicary was never able to replicate these findings formally.

- Here’s a cool site that shows scenes that have frames with images appearing and disappearing at a near-imperceivable rate.(There’s even a Fight Club reference here, too!)

- As humans, our eyes can detect visual signals in less than one millisecond; in camera-speak, this would be a frame rate of 1,000 frames per second! Interestingly, because of how our technology works, refresh rates limit this to about 60 frames per second.

- Different frame rates work better for different formats. For example, “for live TV, sports, or soap operas, 30fps is common. 30fps has six more frames per second than 24fps, giving it a smoother feel that works well for live TV, but it is less cinematic.”

- T-CUP, known as the world’s fastest camera is able to capture images at a rate of 10 TRILLION frames per second. Because of its design, it allows researches to view and analyze processes that may occur too quickly to study otherwise. To learn more about the impressive T-CUP camera, check out this article.

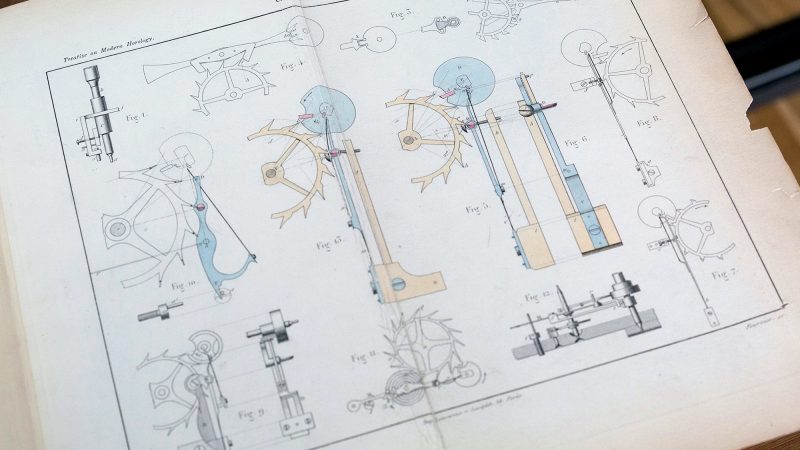

- A number of other optical illusion toys exist that have been around for over a century, including: the phenakistiscope, the zoopraxiscope, the zoetrope, and the praxinoscope.

- Finally, to check out and play with layers of images that allow you to manipulate their frame rates separately, check out this awesome site.